England has one of the highest coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) death tolls in the developed world, and studies show that the COVID-19 pandemic may substantially widen the existing inequalities in national health.

Although some risk factors for increased risk of COVID-19 mortality have been identified, not much is known about the characteristics that make some communities vulnerable and others resilient to the mortality impact of the pandemic.

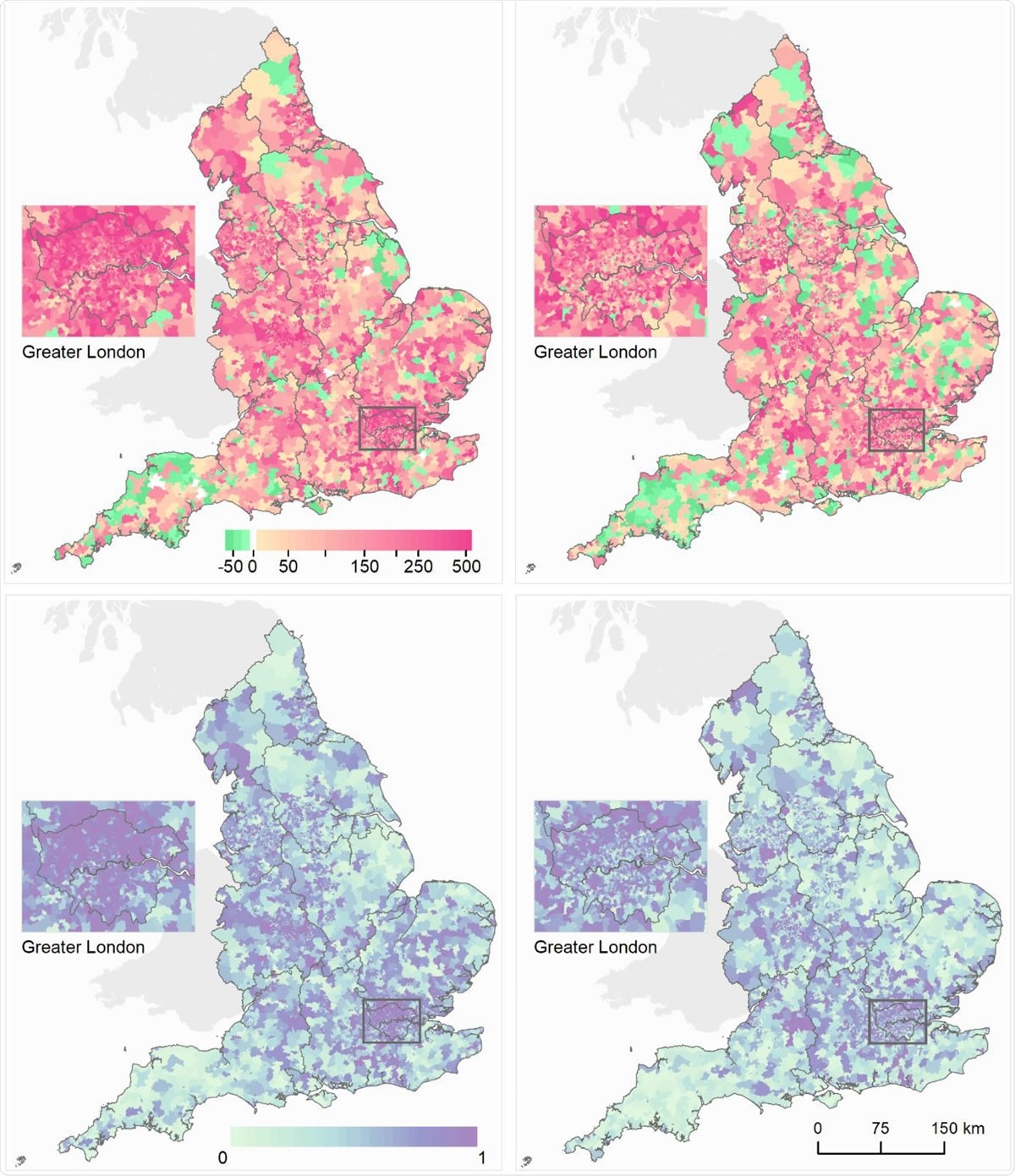

Studies show that the impacts of the pandemic may disproportionately affect the population groups that need healthcare the most, namely, people with chronic health conditions, the elderly, people belonging to a minority ethnic background, and people living in more deprived areas. The number of confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, COVID-19 disease cases, and related deaths vary significantly across England.

Two factors that are deemed significant contributors to increased COVID-19 mortality in industrialized countries are population density and urbanization. However, the local variations in pandemic-related mortality or their community determinants are poorly understood.

Determining local variations in excess COVID-19 mortality

In a paper published on the preprint server medRxiv*, researchers from various departments of Imperial College London, UK, discuss how they analyzed mortality data of individuals 40 years and above in local communities in England to determine local variations in increased mortality during the first wave of the pandemic – between 1 March and 31 May 2020 – and to identify the community factors associated with these mortality patterns.

The researchers applied a two-stage Bayesian spatial model to study the inequalities in excess mortality at the community level during the first few months of the pandemic. They used geocoded data on COVID-19-related deaths in 6,791 local communities between March and May 2020 and compared it to the 2015-2019 period.

Poor communities with overcrowded homes are more susceptible to excess COVID-19 mortality

The study showed that communities with an increased risk of excess COVID-19 mortality had a high density of care homes or a high proportion of residents living in overcrowded homes or a high percentage of people belonging to Black, Asian, and other minority ethnic groups or living on income support.

However, no association was found between air pollution or population density and increased mortality. Overall, the environmental and social variables accounted for about 15% of the differences in mortality at the community level.

The findings of this study highlight the importance of care home density as a predictor of excess mortality in the local community, and this is consistent with the National Health Service policy to discharge nearly 15,000 medically fit in-patients to avoid overwhelming the hospitals.

The authors feel that it is likely that many elderly individuals discharged as part of the policy may have needed support from care homes on discharge and may not have been tested for the COVID-19 prior to discharge.

Higher exposure and insufficient access to healthcare increase mortality risk in some communities

The study also reveals the associations between poverty, non-White ethnicity, and overcrowded housing and excess mortality at the community level. Individuals living in poor and overcrowded communities have fewer opportunities for adopting measures that help reduce transmission, such as social distancing.

“Our study also underlines the associations between excess mortality and poverty, non-White ethnicity, and overcrowded housing at the community-level.”

In addition to higher exposure to the virus, they may also have insufficient access to healthcare for treating COVID-19 as well as other illnesses. Several ongoing research studies indicate that higher mortality risks associated with ethnicity may be a reflection of higher representation in frontline health care jobs, poorer access to healthcare, and potentially higher incidence of co-morbidities such as obesity and diabetes.

The authors believe that timely and effective public health measures targeting at-risk communities are urgently needed in England and other developed countries to avoid the widening of inequalities in mortality risk during the second wave of the pandemic. Further research that throws light on the pathways behind these associations is needed to devise a long-term strategy to address the social and environmental factors of inequality that causes differential mortality during the COIVD-19 pandemic.

“In parallel, economic interventions that support job security and provide financial compensation to low-paid workers required to self-isolate are essential to support population-level compliance with public health advice.”

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.