I started taking the pill in my teens. Most of the girls I knew at my high school were prescribed it, too, whether or not they were sexually active. My doctor told me that there were other benefits aside from preventing ovulation and avoiding pregnancy: It would make my period lighter and the cramps less painful. I could even skip my period altogether by taking it continuously. She also said the pill could lower my risk of ovarian and uterine cancers later in life. Some of my friends took it to alleviate acne. I faithfully refilled my prescription for 20 years, never questioning it, and stopping only when my husband and I started trying for a baby.

We now have two daughters, ages six and four, and no desire for more kids—but for some reason, I’m hesitant to go back on the pill, or any type of hormonal birth control, really. My little pale-pink tablets fulfilled their feminist promise to me—and millions of other women around the world—by giving us control over our fertility and our sex lives. But now that I’ve gone through pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding and weaning twice, and I fully understand the influence that hormones have over my body (as well as the havoc they can wreak), I feel like I’m just done messing with mine. I don’t want to ingest synthetic hormones that could contribute to mood swings or weight gain. I’m also more aware of my body than I was in my teens and 20s, and even in my early 30s. Paying attention to my own reproductive cycle suddenly feels important to me.

Many millennial and late–Gen X women like me (if you were born between 1981 and 1996, you’re a millennial; if you were born between 1961 and 1981, you’re Gen X) are becoming more savvy about their health, and they take their wellness seriously. I’m not talking about the Goop-inspired kinds of “wellness” that involve inserting jade eggs into your vagina—but I do think we are more aware of the chemicals in both the food we eat and the pharmaceuticals in our medicine cabinet. And we’re lusting for birth control that’s better than what our mothers had: We want something easier than a pill you have to remember to take at the exact same time every day in order for it to work, and we don’t want to deal with potential side effects that could impact our bodies and our sex drives.

We also have access to new tools that empower us to learn more about our own fertility: smartphones we keep in our pockets and in our purses, loaded with period-predicting apps. We have high-tech bracelets, watches and other wearable technology that track our cycles and tell us when we’re ovulating. None of these options were available to women even 10 years ago.

All of these factors are causing us to question and research which birth control methods truly work best for us. There are two trends happening concurrently: We want contraception that’s more convenient and delivers lower doses of hormones than the traditional pill. And increasingly, our generation is choosing intrauterine devices (IUDS), which can be hormone-free or contain lower doses of hormones than most oral contraceptives (depending on the type of IUD you choose).

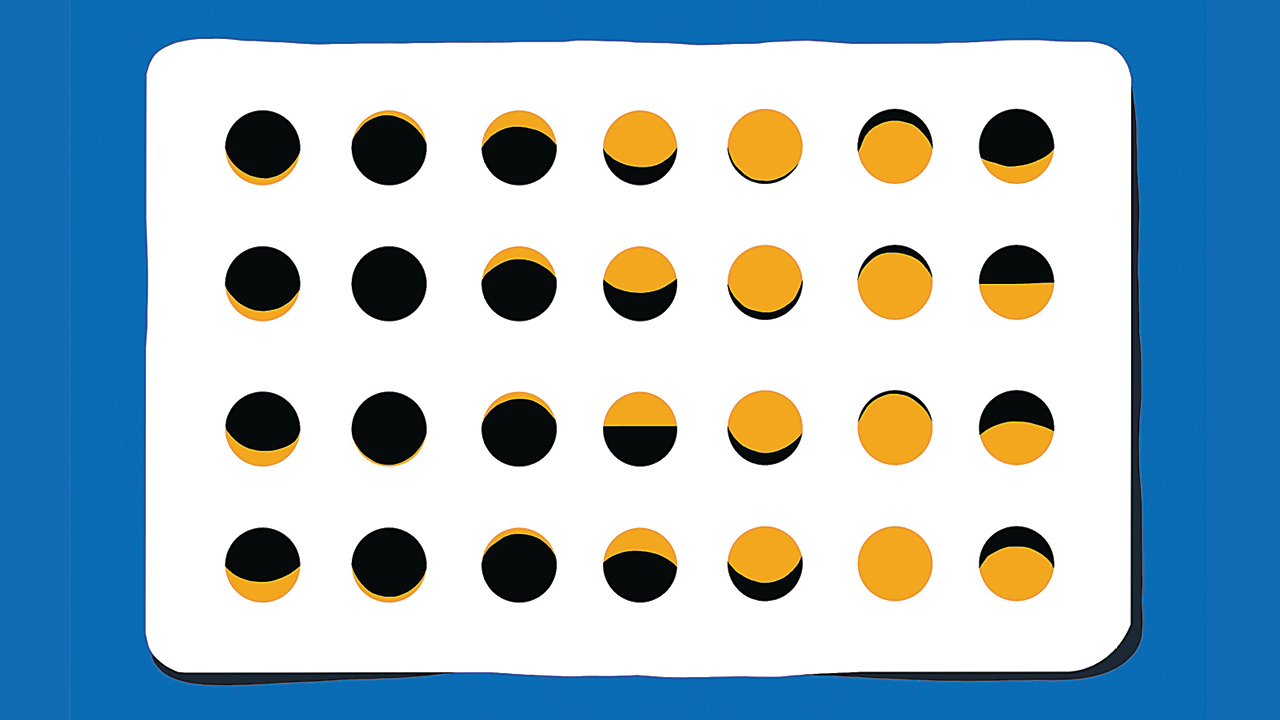

Illustration: Julien Posture

How are IUDs different from the pill?

The two hormones used in the combined contraceptive pill are synthetic versions of progesterone and estrogen. They help keep the natural levels of these hormones in your body constant so that the egg doesn’t mature and you don’t ovulate. They also thicken your cervical mucus, which helps block sperm from reaching an egg. You can also get combined contraceptives in a non-pill form, such as the NuvaRing or the Ortho Evra skin patch. (You can insert the NuvaRing or apply the skin patch yourself.)

Hormonal IUDs like Mirena, Jaydess and Kyleena do contain synthetic hormones, but not as much as the traditional pill does. Instead, they deliver a small dose of progestin, the synthetic version of progesterone, directly to the uterus, and no estrogen. Copper IUDs (sometimes called hormone-free IUDs) don’t contain synthetic hormones at all; they prevent pregnancy by producing a mild inflammatory reaction to the extremely low-level toxicity of copper (which is perfectly safe for the wearer). Experts believe the inflammatory response cues the body to not release any new eggs.

The millennial shift to IUDs

Remarkably, there are no updated, published stats on birth control choices in Canada. The most recent Canadian Contraception Survey data, published by the Journal of Obstretics and Gynaecology Canada, is from 2006—that’s almost 15 years ago. But if we look at the 2015 to 2017 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, we can assume some likely similarities. Their data shows that among the 65 percent of women ages 15 to 49 who were using contraception, the pill was still very popular, but its popularity starts to drop after women turn 20. Longer-acting reversible contraception methods, such as IUDs and what’s called subdermal implants (they’re like little plastic rods, implanted on the inside of your arm, that release low doses of progesterone), are now favoured by women ages 20 to 29, followed by women ages 30 to 39. And the trend is rising: In 1995, for example, less than one percent of women used IUDs, according to the CDC. That number increased to nearly 6 percent by 2010, and the most recent numbers show more than 10 percent of women between 20 and 39 have an IUD.

Using the Canadian Contraception Survey from 2006, we know that the three most popular forms of contraception back then were condoms, the pill and withdrawal. (Other options mentioned in the survey include more permanent methods, such as vasectomies and tubal ligation, and natural family planning, also known as the rhythm method.) A more recent 10-year comparison study, also published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada in 2016, focuses only on Canadian adolescents. But it found that the use of condoms increased—from 51 percent in 2006 to 71 percent in 2016—while oral contraceptives greatly decreased—69 percent to 32 percent in the same time span. (The withdrawal method remained unchanged, at about 16 percent.) But doctors say the outdated and sporadic Canadian data doesn’t capture two of the most significant shifts they’re seeing among their patients—the popularity of IUDs (either hormonal or non-hormonal) and the move away from the traditional birth control pill.

“We are seeing a trend away from hormonal, and certainly pill-based, contraception,” says Dustin Costescu, an OB/GYN and associate professor in family planning and sexual medicine at McMaster University Medical Centre in Hamilton, Ont. “Certainly with IUDs, young people are using them and some are even using them as their first method of birth control, which is really different from the historical practice of starting with the pill and maybe getting an IUD when you’re done having kids.”

Costescu explains that from the ’60s to the ’90s, IUDs were primarily studied in women who had already been pregnant. The devices were larger than they are now, and in the early days of the IUD, in the 1970s, some brands were troubled by recalls and scandals after women developed pelvic infections from them. (Back then, medical devices like IUDs weren’t vetted by health regulators.) They were shaped like coils, squiggles or plastic “shields” and ranged from about three to five centimetres—designed for placement immediately after childbirth while the uterus was still expanded from pregnancy. Plastic IUDs are still flexible, notes Cotestcu; as the uterus contracts and gets smaller in the weeks after having a baby, the IUD also compresses.

These days, the newer T-shaped models are just under three centimetres—the perfect fit for a uterus—and can be inserted by a specialist in a few minutes. Some women experience pain during the procedure or cramps in the days following. (This depends on your pain tolerance, the size of your cervix, and how experienced the care provider is at doing insertions.)

After the IUD is in, however, you or your partner shouldn’t be able to feel it during sex, and it’s 98 to 99 percent effective in preventing pregnancy. (The strings of the IUD get trimmed after insertion, and extend below your cervix, inside your vagina, but they do not hang outside the vulva.) You can keep an IUD in for anywhere between three and 10 years, depending on the type and brand: Hormonal IUDs like Mirena last three to five years, while hormone-free IUDs last five to 10 years.

“This whole idea of long-term birth control before your first child is a relatively new concept,” explains Costescu. “In the ’80s and ’90s, you would become sexually active at 16 or 17, and then have your first kid at 21. Now, in the 2000s and beyond, people are still sexually active at 16 or 17, but they’re not having their first kid till 30.” In 2018, the Canadian Paediatric Society released a position statement that officially recommends IUDS for sexually active teens.

Amanda Selk, an OB/GYN at both Women’s College Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, says birth control choice also comes down to how doctors counsel their patients. “IUDs are more and more encouraged because they’re shown to have very high success rates and patients report longer-term happiness with them.” The more women hear positive experiences from their friends, the more popular they’ll become, says Selk.

North America is simply catching up to the IUD’s ubiquity elsewhere—they have been big in Europe and Asia for decades, she adds. “In China, that was how they controlled their one-baby policy. Everyone who had a baby got a copper IUD. They were put in whether people wanted them or not,” she says.

IUDs are also cost-effective when you consider how long they last: Copper IUDs cost between $60 and $200 upfront, but you’ll have it in for 10 years. Hormonal IUDs cost $400 to $500, and you’ll only pay that once every three to five years. (Some private medical plans cover some, or all, of the cost of an IUD.) Regular birth control pills cost around $30 a month, but that works out to $360 a year.

Costescu, a millennial himself, says the set-it-and-forget-it nature of IUDs is a big plus. “Millennials are busy, and we know that the pill is something that’s hard to remember to do every single day.”

When your doctor removes your IUD (you can’t do this yourself), your fertility should return to normal within a few months if you had a hormonal IUD, or right away, if you had a copper IUD. This is why it’s a myth that you can’t use IUDs for spacing out pregnancies during your childbearing years. (You can also breastfeed safely with an IUD inserted—the progestin in a hormonal IUD shouldn’t affect your milk supply or your baby.)

If you’re planning to get pregnant again before your baby’s first birthday, shorter-acting methods such as the pill, condoms or even withdrawal would be the best birth control options. But if you’re waiting any longer than a year to try for another kid, an IUD in between pregnancies is a definite possibility, says Costescu.

What are the side effects of hormonal birth control?

The current medical consensus is that the majority of women do not experience adverse side effects from hormonal birth control, whether it’s the traditional pill or a hormonal IUD. The more serious risks of combined contraceptives you may have heard about apply to women who are already at increased risk of stroke and blood clots or are smokers over the age of 35. The less scary, but more common, side effects of hormonal birth control are generally mild: sore breasts, nausea, headaches and spotting or bleeding between periods. (Spotting is more common with progestin-only pills, also called the “mini-pill.”)

There is less conclusive data on the pill’s subtler, more subjective side effects. But talk to any of your girlfriends and you’ll hear all about changes to our mood, mental health, body image and sex life. Millennial moms I spoke with said they experienced weight gain, a “flat mood,” depression and a decidedly lower sex drive while on hormonal birth control. Others felt that synthetic hormones were masking their ability to feel more in touch with their bodies, including their cycles and when they were ovulating.

Sarah E. Hill, an evolutionary psychology researcher and the author of This Is Your Brain on Birth Control, says that sex hormones affect brain function in so many ways—from what you find pleasurable to who you find attractive. “There is no area in the body that has more receptors for sex hormones than the brain,” she says. “When you take the pill or any other form of hormonal birth control, you change the version of a woman that your brain creates—a different version of you.”

For Virginie Lanoix, 34, a mom in Montreal, the effect contraception has on her libido is one of her dealbreakers. She works as a registered nurse in obstetrics and has tried many different kinds of birth control. She started on the pill as a teen, but it made her nauseous, so in her early 20s, she switched to the NuvaRing before noticing it was lowering her sex drive. Then she tried a low-hormone IUD, which also lowered her libido and caused spotting.

“Sex is a passion for me,” says Lanoix. “I wasn’t feeling like myself on hormones. Every time I quit the hormones, I would have a higher sex drive—more intense, more often, more instinctive,” she says. “I also noticed my libido is always much higher around my ovulation. It’s like my body trying to get me pregnant, even though I don’t want another kid!”

After Lanoix had her son, who’s now two, she had a non-hormonal copper IUD installed. Although it’s caused her periods to be heavier, she says it’s been worth it to get her libido back.

Hill explains that one of the ways hormonal birth control can be like “anti-venom” for your sex drive is that is suppresses the natural ovulation and estrogen that would normally be motivating your brain to get in the mood.

The way in which women respond to different hormonal birth control methods is individual and not well understood, but a growing body of research suggests mood changes can result from both combined-hormone pills or progestin-only birth control, including IUDs and the mini-pill. For some women, the mood changes can be severe.

Chelsea Sharpe*, a 36-year-old mother of two from Toronto, had a hormonal IUD put in when her firstborn was four months old, on the advice of her regular OB/GYN. She had it removed four weeks later.

“I couldn’t stop crying,” she remembers. She says that she didn’t have any postpartum depression symptoms or issues with mood stability before the IUD. “The day I booked the appointment to get it taken out, I had been crying for three hours while my baby, who napped like a champ, was sleeping. I was acutely aware that I wasn’t actually sad or bothered by anything. I just had these raw, disconnected emotions and I quickly connected the dots.”

The OB/GYN who removed Sharpe’s IUD told her that while she didn’t have data on it, anecdotally, she’d heard of these IUD-related depressive symptoms happening a lot.

For Michelle Harmon,* a 36-year-old Ottawa mom with a three-year-old, a combination of reasons, including a family history of breast cancer, made her second-guess her contraception choices. “I was on hormonal birth control forever—I started very young because I had terrible cramps during my periods,” she says. She went on and off a few times in her late 20s for different health reasons. She doesn’t want anymore kids, but she’s hesitant to take any medications that tinker with her hormones after experiencing an unexplained seizure during childbirth with her daughter.

Costescu says that his patients do ask him about a possible link between birth control and breast cancer, but there’s no simple answer. “High-quality studies fail to show an increased risk of breast cancer solely from using birth control,” he says. “There are many factors that can affect breast cancer risk, including delaying pregnancy to after 40, not breastfeeding and your lifetime number of pregnancies. Birth control affects these parameters as well.”

Harmon considered getting a copper IUD but decided that wasn’t a good option for her either, because her period cramps are already bad and it would likely make them worse. “For the last three and a half years, my husband and I have been doing the very responsible thing and barely having sex,” Harmon jokes. “When we do, we use the rhythm method and ‘pulling out’ like 16-year-olds.” They also decided her husband will eventually get a vasectomy, though they haven’t booked an appointment yet.

Your right to choose

With so many birth control options available, it’s important to speak with your family doctor, OB/GYN or other health professional about the pros and cons of each method. The Sex and U site from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) has a handy quiz that can help you find the best type of contraceptive for you, based on your age, health risks, period symptoms, your history with different contraceptives, your comfort level with hormones and how important it is for you not to get pregnant. If you know you definitely don’t want anything with hormones, you can talk to your doctor or healthcare professional about that, too.

“At least half of the women I see are no longer interested in using hormonal birth control,” says Jada MacLeod, a licensed naturopathic doctor in Ottawa who focuses on women’s health and fertility issues. (She admits those numbers may be biased because her clients are seeking out a naturopath to begin with.) MacLeod sees many postpartum women who don’t want to deal with any more hormone fluctuations after having a baby. “The most common reasons that women will stop hormonal birth control are mood and libido. A lot of women will find that they get depressed, and they have absolutely no interest in sex.”

MacLeod counsels her patients about using the rhythm method, which can be tricky postpartum, she warns. If you’re breastfeeding and your period hasn’t returned yet, it’s impossible to track your menstruation for several months to know when you’re ovulating and fertile. And, MacLeod adds, if you tend to have an irregular cycle anyway, or you’re over 35, apps alone are not reliable for predicting when you’re most fertile, so you should avoid unprotected sex. “I end up doing a lot of educating around all of that,” she says. Besides teaching her clients about the signs of ovulation, MacLeod also looks at nutrition and lifestyle (like stress levels and sleep habits) and will often prescribe different vitamins and herbal medicines to help with regulating and predicting periods. “And I let women know that nothing is quite as effective as hormonal birth control,” she adds.

As cool and worry-free as IUDs or implants may sound to some, I’ve decided to stick with the hormone-free birth control method that’s been working for us: I track my periods on an app and my husband and I use condoms, especially if I’m anywhere near my fertile window. Barrier methods like condoms may feel kind of old school, but neither of us is ready to undergo a permanent procedure, I have no interest in having a foreign object inserted in my body, and I just feel done with hormones. At this point in my life, going back on the pill would be tough to swallow.

*Names have been changed.

Editor’s note:

We hope you enjoyed reading this article from Today’s Parent. We’re working hard to provide our readers with daily digital articles that aim to inform, inspire and entertain you.

But content is not free. It’s built on the hard work and dedication of writers, editors and production staff. Can we ask for your support? We are currently offering 3 issues of the print edition of Today’s Parent for only $5. A subscription also makes a great gift for that new parent in your life.

Our magazine has endured for more than 35 years by investing in important parenting stories. If you can, please make a contribution to our continued future and subscribe here.

Thank you.

Kim Shiffman

Editor-in-Chief, Today’s Parent