Soon after John and Priya Miller* discovered they were expecting a second child, they knew they’d have to get their first-born, then 18 months old, on a sleep schedule—fast.

Aria had been zooming through milestones (walking at nine months and speaking in short sentences by 12 months), but sleep remained a struggle. The strong-willed toddler resisted an early bedtime and seemed just like her dad, a self-described night owl.

From the time she was three months old, Aria didn’t get to sleep until 11 p.m. or midnight, but since Priya wasn’t working outside the house and John was self-employed, Aria could sleep in until 8 or 9 a.m. “When she was really little, we’d roll with her sleep schedule,” says John. “We just wanted her to get a block of sleep that was reasonable.” But this wouldn’t work so well with an infant in the mix.

After reading books, talking to Aria’s paediatrician and scouring the internet, the couple bravely embarked on their mission to teach Aria to fall asleep at a more normal hour. For three months, Aria resisted every strategy they attempted; in fact, for the first 40 days or so that they tried the cry-it-out (CIO) or extinction method, she would cry so long and so hard that she’d throw up in her crib. “My god, she fought us so hard,” says Priya. “We did a lot of laundry,” John adds. Despite the couple’s best efforts, they abandoned the intense sleep training and Aria was still a night owl at 26 months, when baby number two arrived. She has remained so through her childhood.

Chronotypes and kids

While bedtime struggles seem like a parenting rite of passage, research shows that some kids are “wired” to stay up late, just as others rise with the sun. These sleep tendencies are known as “chronotypes”—a concept that has been studied extensively since being coined by Swedish researcher Oscar Öquist in 1970. There are four main categories of chronotypes: larks, morning types, evening types and owls, although some researchers break those categories down even further. One author, clinical psychologist Michael Breus, classifies them as animals. A lion is a morning person; wolves enjoy staying up late. Bears avoid extremes (both late nights and early mornings). Dolphins are those with sleep problems: anyone with inconsistent sleep or who wakes up feeling unrefreshed, kids who struggle to nap and those who get a spurt of energy in the evening.

Chronotypes vary by individual, but they change predictably over the human life cycle. As children, we are more prone to what sleep experts call “morningness,” but we shift toward “eveningness” by adolescence (which supports the argument that high schools should start later). By adulthood, most people have shifted toward morningness again.

Child psychologist Penny Corkum, a sleep researcher at Dalhousie University in Halifax, says that these tendencies are as much the product of nature as nurture—both are at play. Individual genetics strongly influence how our internal clock is set, but environmental cues—like light exposure from screens at night—can affect our sleep patterns significantly. “The nice thing about most of our biology is that it’s somewhat flexible to our environment, because that’s what makes us adaptable,” says Corkum.

Whether you’re a child or an adult, the default setting on your internal clock can be reprogrammed, she says. Almost anyone who needs to get to sleep earlier in order to get enough hours of sleep before their alarm chimes can shift to a new schedule with the right strategies (the exception being those with diagnosed sleep disorders—more about that later). Corkum points out that research also shows we get better-quality rest in the hours before midnight—going to bed earlier is better for us than sleeping in.

Reprogramming our internal clocks

Parents of suspected night owls or evening types will likely never get confirmation of this from a healthcare professional. That’s because chronotypes are difficult to assess in children due in part to a lack of research and the simple fact that kids’ schedules are decided by parents. While you can ask an adult questions about their sleep habits and preferences—like how long they sleep in during the weekend or their ideal time to take an exam or get complex work done—a child can’t give meaningful answers.

Fortunately, most parents don’t need this information to help their kids. Regardless of whether you think you’re raising a night owl or a morning lark, behavioural modifications can make a tremendous difference to when and how well your child sleeps.

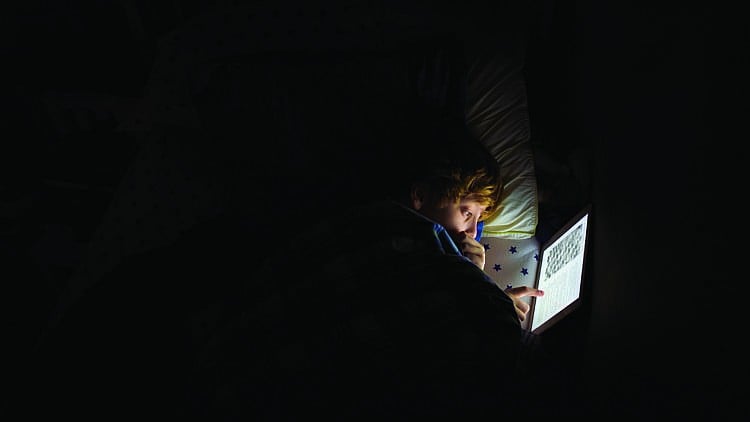

Our circadian clocks are primarily set by light and darkness, which means we can help kids adjust to earlier bedtimes with strategies like early-morning exposure to bright light and ending screen time at least one hour before bed. The latter is likely the most effective way to improve sleep, she says, as research shows the blue light emitted by phones, tablets and other devices prevents children’s brains from producing enough of the hormone melatonin, which triggers sleepiness. To make matters worse, screen time also stimulates kids’ brains at a time when they need to be calming down.

COVID-19 has not helped. “We’re all home on our computers and devices, and everything’s portable,” says Corkum. It’s also not as simple as wearing blue-light glasses or adding a blue-light blocker app to your phone or computer screen—these won’t address the amount of visual stimulation caused by the device and the lack of physical activity. She suggests parents lead by example and join their kids in putting away electronics and screens well before bedtime—try to leave everyone’s devices in the same spot in a separate room each night.

Kids also benefit from a predictable bedtime routine and consistent schedules and wake times—on both school days and weekends. “It’s not just about changing things at nighttime—it’s about what happens in the daytime, too,” Corkum says, including exercise and meals. Kids should go to bed feeling neither full, nor hungry, she says. A small snack of a protein and a carbohydrate, such as cheese and crackers, or peanut butter on toast, is ideal. Offer it at the beginning of the routine—about 30 to 60 minutes before lights out.

Corkum advises parents to follow the new Canadian 24-hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth released by ParticipACTION. For kids and teens, the guidelines now recommend 60 minutes per day of moderate to vigorous physical activity (like bouncing on a trampoline or playing soccer), several hours of light physical activity (like helping with chores or flying a kite), and no more than two hours per day of sedentary activity (like playing on a tablet or watching TV).

This 24-hour perspective is also at the heart of Better Nights, Better Days, an e-health program for parents of children with difficulties falling or staying asleep. Shelly Weiss, a paediatric neurologist at the Hospital for Sick Children and professor at University of Toronto, developed it with a team of sleep experts from across Canada. The interventions are delivered online to participants ages 1-10 over the course of six to 10 weeks, with a focus on sleeping better, creating resiliency and improving kids’ overall functioning despite COVID-19 lifestyle changes.

“Through the software we’ve developed, [families] get personalized information on what they’re doing well and what they can do to make changes,” says Weiss. In her experience, parents can almost always solve their children’s sleep problems by being consistent, patient and firm. “Usually it comes down to scheduling, putting limits on children, and good bedtime routines,” she says.

As trying as it can be, it’s worth the effort. “A child who isn’t getting enough sleep can have trouble with learning, memory, socialization, attention, and behavioural and emotional regulation,” explains Weiss. The effects of chronic sleep debt can even mimic the symptoms of ADHD.

Weiss warns against resorting to melatonin supplements to help kids sleep better, even if you’ve heard other parents singing its praises. “Kids who are typically developing shouldn’t be taking melatonin at night,” she says.

Are sleep disorders common in kids?

Like adults, kids can have underlying physical or mental health problems, like anxiety, that prevent them from falling or staying asleep. But sleep disorders like sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome are fairly unusual in children. Sleep apnea can cause frequent “rousing” periods, which would make kids feel less rested when they wake up, but it wouldn’t impact how easy it is for them to fall asleep at the beginning of the night.

There’s a difference between a a night-owl kid who drifts off a bit later than most kids their age versus the night-owl child who’s consistently up past midnight, Weiss explains. “Having a later chronotype makes a child go to bed 30 to 45 minutes later [than most kids], not a full two hours later.” (One note: If your child is still napping, your first step is to cut out the nap, obviously.)

Children with schedules that consistently resemble an adult night owl—staying up until the wee hours of the night—may actually have a sleep disorder. It’s called delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD), and it’s very rare, though it can run in families. With DSWPD, the onset of sleep is delayed due to a delayed secretion of melatonin. This is more likely in adolescence, when our chronotypes naturally shift toward eveningness, largely in response to biological changes during puberty.

Both Corkum and Weiss emphasize that the vast majority of night-owl kids don’t have diagnosable disorders—just stubborn habits that can change with lots of parental effort, and sometimes, expert help. If you need more support, don’t hesitate to seek advice from a healthcare professional, such as your family doctor or paediatrician, and check out the sleep experts on the website of the Canadian Sleep Society.

*Names have been changed.