When I was a little girl, my appendix burst during surgery and I almost died on the operating table. My recovery was slow and complicated—my parents didn’t know if I’d live. During the weeks when I was in bed at the hospital—in great pain—my mom read a story to me about an older girl who grew up in the foster care system. She was afraid to be loved, but a couple took her in, gained her trust and eventually adopted her. I loved that story and I remember thinking, If I get through this, I want to grow up to be just like the mother in that book.

I never wavered from that goal. Today, my husband and I have eight kids—a mix of biological, fostered and adopted children. Our youngest daughter, Kira, came to us at six weeks as a foster child. She is “Omàmiwininìwag,” which is Algonquin (Indigenous people of southern Quebec and eastern Ontario), and she changed the course of of our lives in ways I never could have imagined.

I have Indigenous ancestry: I’m Métis and Ojibwe on my mother’s side, but I grew up Baptist because my mother and father converted when I was young. I had a happy—albeit very conservative—upbringing. Our church was independent and had strict rules: We had to dress modestly, and no dancing was allowed. My lifestyle was vastly different from that of my cousins on my mother’s side, and I believe my mom made an unspoken decision to create some distance due to problems with alcoholism in the family. But this also meant that I lost my connection to Indigenous traditions and wisdom.

We rarely spoke about our Indigenous heritage. As an adult, I heard stories at my grandmother’s funeral about how she used to love to dance. Another time, my great-aunt spoke of my grandmother bathing her in a cedar-infused bath. It was fascinating and foreign from the life I knew.

By the time I was married and had several kids of my own, I had all but forgotten my roots. That dramatically changed after my husband and I met Kira in the neonatal intensive care unit when she was four weeks old.

Kira’s birth mother had used various drugs, so she was apprehended at birth and cared for in the hospital while she went through withdrawal. When we first saw her, she was lying in an incubator on morphine in the darkest corner of the ward. She was in pain, and she still had tremors. The hospital staff hesitated to let us into the room—they thought it would be too traumatic for us. But I persuaded them and, when I was finally able to cuddle her, it was instant love. She was so beautiful with her dark complexion and soft black hair, and she looked just like my biological kids looked as babies. I said to my husband, “Oh, honey, I’m in so much trouble with this one. I feel like she is meant to be ours.” She wrapped her tiny hand around my husband’s finger. He was smitten, too.

The Children’s Aid Society (CAS) planned to place Kira with her two older siblings in an adoptive family. Her foster placement with us was supposed to be for just a few weeks. After she came home from the hospital, I took her to a photo studio, knowing that the adoptive family would want baby pictures. When the portraits were printed and framed, I showed them to Kira’s case worker. She looked at me with surprise. “Did no one tell you?” she said. “The adoptive family has changed their mind.” Immediately, I jumped in. “Can we adopt her?” I asked.

As we started the application process, our workers kept saying “We support your adoption plan, but you have to understand that if the band finds another family, we have to consider them, too, so this may not happen.” The band is the governing body of First Nations groups, and they have a say in where Indigenous children are placed. Their top requirement is a good cultural match. I hadn’t even mentioned my First Nations ancestry on the forms—it seemed wrong at the time because I was so disconnected from it.

There was no knowing how things would turn out, but regardless of how long Kira would stay with us, I was committed to helping her grow up to be a proud First Nations woman. To me, the cultural tourism approach didn’t feel like enough. There are some things in life I go after with unstoppable determination. (Becoming a foster parent at age 20 is a good example: My husband and I were told to wait until we were 30 when we inquired to the CAS at ages 21 and 19 respectively, but we ignored the rules, did the training and somehow got approved.) Making sure that Kira had a meaningful immersion in her culture was so important to me that I was ready to overcome my own fears of feeling like an imposter and dive right in.

I was nervous about my first powwow, and I did a lot of online research to make sure I knew the proper etiquette. But I was mesmerized as soon as I heard a large group of women sing together. They stood in a circle, facing inward, with their backs to the crowd so that they could really focus on one another and blend their voices perfectly. The drumming was like a heartbeat: It was so powerful, and I remember wishing I could belong in that circle, too. Even though I hadn’t grown up with Indigenous music, the longing I felt made me feel as if the memory of the songs was somehow in my blood.

Soon, I was signing up to volunteer at powwows—the organizers always needed help. One time, I happened to volunteer alongside a man who had been adopted as a child in the 1970s by a Christian family and things had fallen apart. He held a lot of anger and was trying to reconnect with his First Nations roots. Our conversation left me all the more anxious to do right by Kira and keep her close to her community.

I joined that drumming group and got to know all those strong women who I count among my closest friends today. Then I learned beadwork. Now, six years later, I actually teach people how to make the beautiful and intricate beaded outfits that dancers wear.

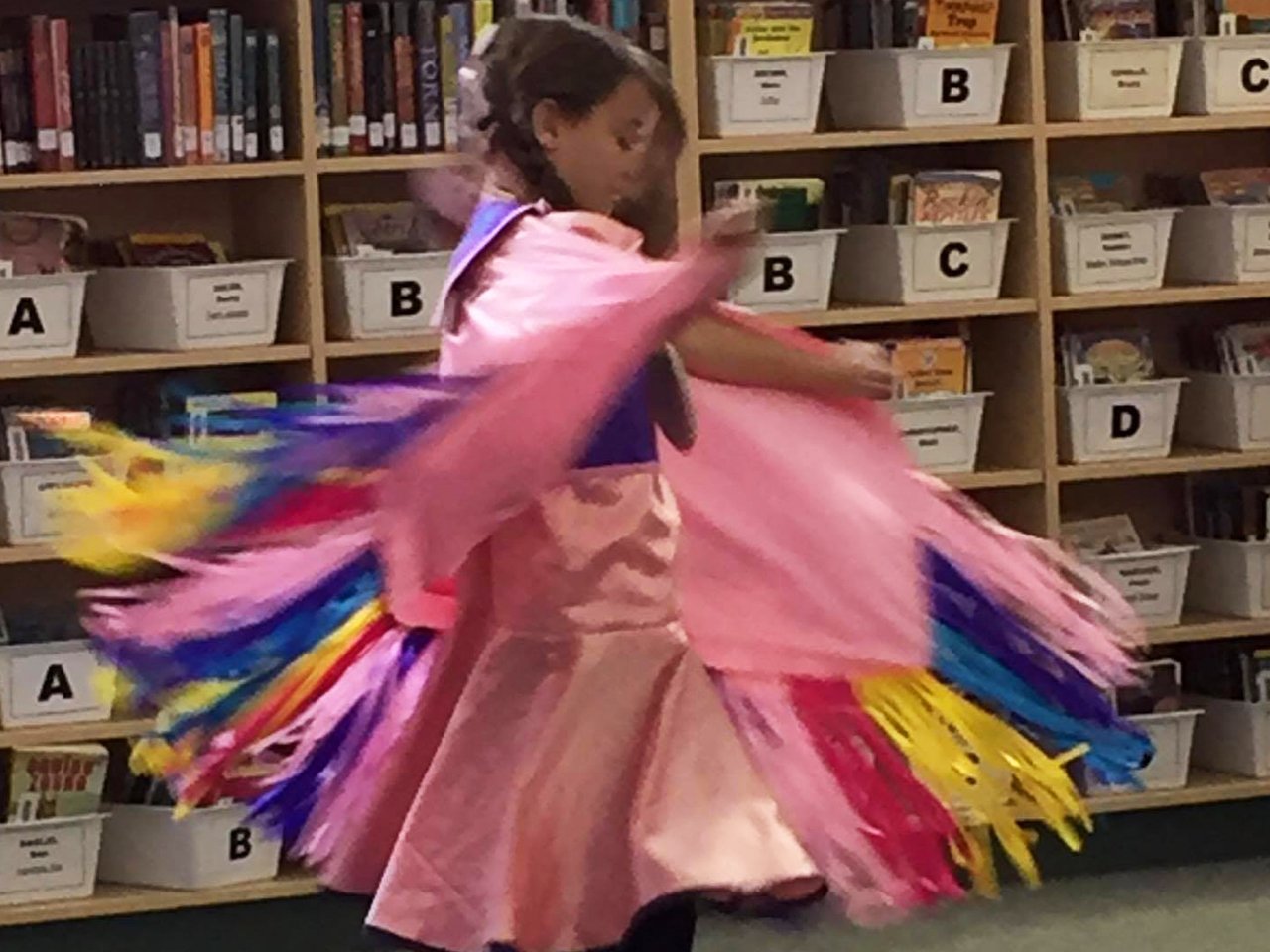

Photo: Courtesy of Stacey Moffatt*

I love seeing kids wear things I’ve made. One young woman, who was head junior dancer and had grown up in the community, once wore earrings that I’d made to perform. I felt so honoured. Sometimes I lend beadwork or regalia that I’ve made to kids who grew up outside of their Indigenous communities—often in foster care—and are coming to powwows in the hope of reconnecting with their roots. They seem nervous at first in this unfamiliar attire, but their eyes shine when they come back and tell me that someone asked to take their photos or that one of the elders told them they looked beautiful. I feel proud that in a small way I’m helping them reconnect with their community of origin.

And I can relate. Back when Kira was an infant, I felt like I had so much to learn. I felt scared that I would say or do the wrong thing. After a few months, one kind elder took me aside and said, “It will take you four moons—four seasons—until you start feeling like you have knowledge and you belong.” I just kept showing up, listening to what people had to say and asking questions. Although I’ll never stop learning, the elder’s words turned out to be true: One year later, I finally felt at home in the community.

I started to realize that I needed this connection, not just for my daughter but also for myself and my biological children, who had also been cut off from their ancestry. I began taking online classes to learn the language of my Ojibwe Anishinaabe grandmother, which is similar to the language of Kira’s biological family, who are Algonquin. One of my sons learned it, too, just from participating in activities. One time, he stood up to make a speech at an event and did his whole introduction in Ojibwe. I was so proud—I hadn’t even realized that he was that fluent in the language.

That same son is really shining now as a youth leader and member of the Indigenous youth advisory board. Right before Kira came into our lives, he was struggling with depression. Joining this community seemed like a homecoming for him, too. He is especially fond of teaching traditional grass dances to youth who are returning from foster care and answering their questions as a bridge between the world they’ve known and the Indigenous community they’re trying to get to know.

Photo: Courtesy of Stacey Moffatt*

Another son has come with me to teach First Nations culture at schools. My middle daughter sings now, and she was once given the honour of leading a song for a large group of women. Afterwards, one of the elders gave her a choker to go with her regalia as a thank you gesture. Kira’s favourite thing is dancing at powwows. She spends more time running than dancing, but she watches her sister carefully and tries to follow her lead—it’s a joy to watch. The elder women have become like aunts to all my kids. For Kira, I’m hoping that growing up with all these First Nations people who love her will help mitigate the loss of her birth family.

There’s a teaching in the First Nations community that before a child is born, he or she picks which family they are going to be part of with the purpose of teaching something to that family. I truly believe that Kira picked both her birth family and us.

Kira will have a lot of struggles because of the drugs that her biological mother took during pregnancy—she has brain damage, some developmental delays and sensory sensitivities. When she was tiny and going through withdrawal, I sometimes wondered angrily why her birth mother couldn’t just have stopped taking drugs. I have more empathy now: Her parents had a hard life, and her parents’ parents had a hard life—there have been generations of trauma. Kira’s birth family was deeply affected by the residential school system and the Sixties Scoop, where large numbers of Indigenous children in Canada were taken from their families and fostered and adopted outside of their communities. Many problems ensued, with addiction, abuse and people doing whatever it took to survive under hopeless circumstances.

I’ve built a relationship with Kira’s birth parents by sending letters and photos. Her biological mom has written lovely letters back and, through our correspondence, I’ve come to realize that this young woman was doing the best she could and that she loves Kira deeply, even though she can’t care for her.

Understanding generational trauma shed so much light on my own family, too. I finally understood that opting for such a conservative Christian upbringing was my mom’s way of protecting my brother and me from some of the troubles that our cousins had, even if that meant losing a part of our identity in the process. I’m so grateful to Kira for delivering me and all my children safely back to these vital aspects of who we are.

To take that further, I co-founded a more formal program outside of my regular work with the Toronto-based non-profit organization Adopt4Life. An independent volunteer-based program called Wraparound Families is for for youth aged 16 to 25 who are aging out of foster care. Many of the kids I work with are First Nations or Métis, desperate to return to their communities of origin. I’ve been able to relate and help them find their way back. Over the six years that Kira has been in my life, I’ve gone from barely knowing my own heritage to working to ensure that no Indigenous child who goes into the system has to lose touch with their identity and heritage.

Thanks to my beautiful daughter, life has come full circle.

*Names have been changed. As told to Valerie Howes.

This article was originally published online in January 2018.