Environmental microorganisms play an essential role in human health – the diverse the consortium, the better. Diversity in the microorganisms helps the immune system to respond to pathogens.

It also helps control overstimulation of the immune system in response to innocuous agents, such as dust particles, pollen, and sometimes, our cells – the latter manifesting as autoimmunity. Exposure to these microbiomes from the environment in early childhood is known to help develop a strong immunity.

In addition to better immunity, the diverse microbiomes supplement humans with important functional microorganisms. It is established that soil-derived butyrate-producing bacteria may supplement the gut bacteria and can reduce anxiety. Certain bacteria produce important molecules essential to human health: inhibit tumors and atherosclerosis, improve bone formation, promote epithelial integrity, etc. Also, exposure to plant diversity and associated microbial communities is significantly correlated with reduced risk of acute lymphoblastic leukemia by promoting immune maturation.

Urbanization and loss of macro-biodiversity are linked to loss of microbial diversity, which could negatively impact the health-supporting microbial communities residing in and on human bodies – the human microbiome.

In a recent bioRxiv* preprint paper, Jake M. Robinson and colleagues study the dynamics of ‘aerobiome’ - the collection of microorganisms in a given airspace, with respect to the height from the ground level. The study of the dynamics of near-surface aerobiomes in urban green spaces is minimal. However, studies show that the aerobiomes differ in urban and semi-urban spaces. They are distinct in urban green and grey spaces and are modulated by the vegetation type and are influenced by local changes such as weather or land management.

The researchers have demonstrated aerobiome vertical stratification between ground level and 2 m heights in an urban green space in a previous study.

An individual may be exposed to any kind of aerobiome. Depending on the habitat and height––and their interactions, the diversity and the function of the aerobiome will change. Thus, the effects of different aerobiomes may have implications on individual and public health.

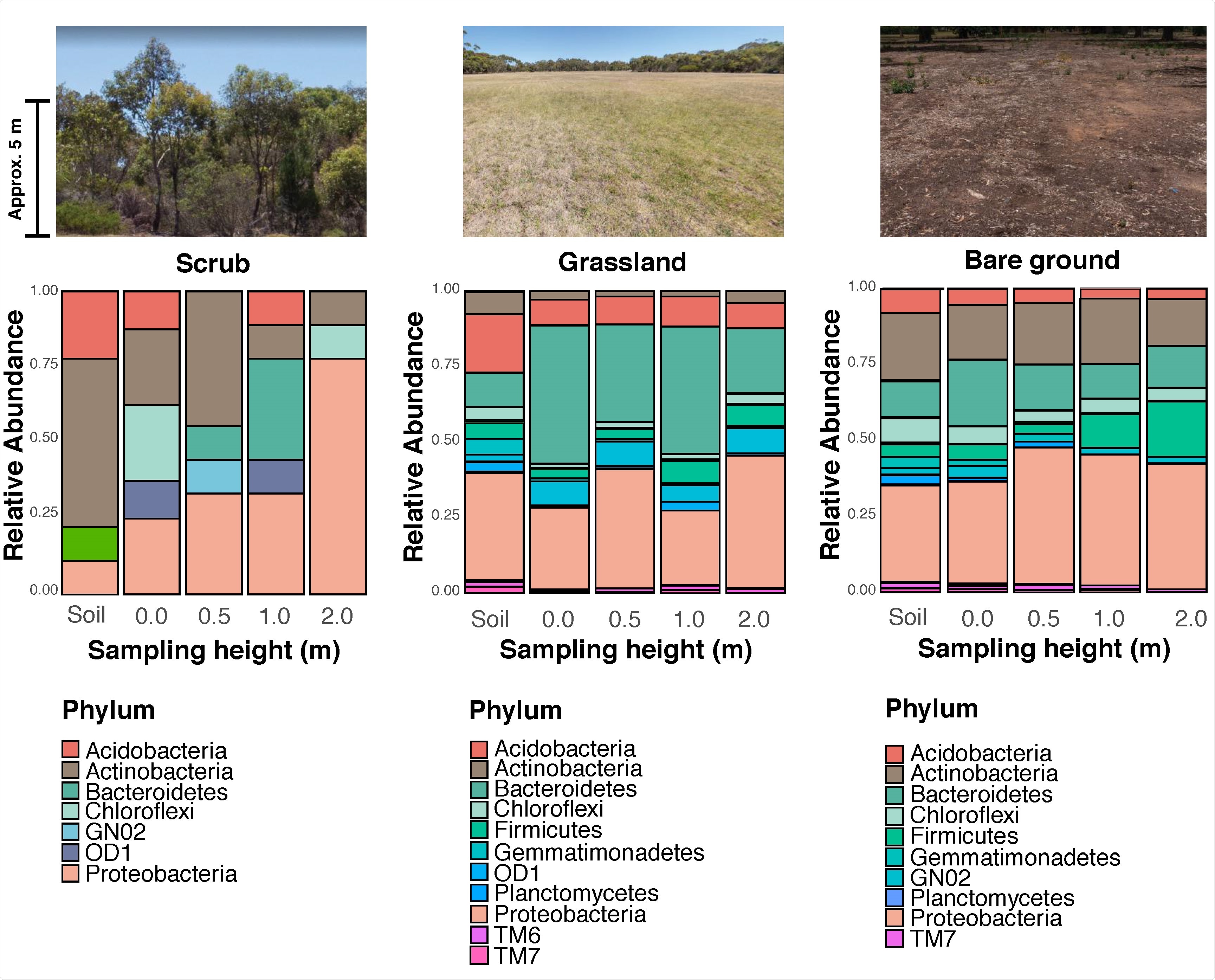

This study focuses on aerobiome bacterial communities. The team used an innovative columnar sampling method to sample aerobiome bacterial communities in three urban green space habitat types in the Adelaide Parklands, South Australia. Their objective was a meticulous comparison and assessment of aerobiomes diversity, vertical stratification, the influence of tree density, and the pathogenic bacterial taxa among the three habitats. The habitats include amenity grasslands, woodland/scrub (dominated by native Eucalyptus spp. trees and shrubs; henceforth referred to as ‘scrub’), and bare ground habitat; each habitat is a typical urban green space habitat.

They characterized the diversity, composition, and network complexity of aerobiomes by using next-generation sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. The authors applied geospatial analytical methods to explore the potential influence of trees on the micro-biodiversity of aerobiomes.

They found the dominant bacterial community in all three habitats: Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria. However, the abundance of the bacteria varied with height. They also found that the scrub aerobiome was more biodiverse than the bare ground; in fact, it had the most biodiverse aerobiome.

The bacterial diversity is reduced on the bare ground with increasing sampling height from ground level to 2 m. The highest diversity was at the soil level.

The authors tested for diversity differences between dates and sites and found no significance in factoring these.

The results show that the aerobiome bacterial community differed significantly between urban green space habitat type. This study shows that aerobiome diversity, composition, and network complexity stratified vertically. This suggests that the potential bacterial exposure and transfer depends on the habitat type as well as the person’s height or behavior.

The study suggests that urban habitats with more complex vegetation communities are more biodiverse. Urban green spaces need to have this vegetation to ensure exposure and transmission of environmentally-derived bacteria to the skin and airways. Because these bacteria are essential for better health, urban planning needs to implement the vegetation spaces intelligently.

The results also confirm that trees and the greater canopy are associated with higher aerobiome diversity. The team found abundant putative pathogenic taxa significantly different in proportions between grassland and scrub habitat samples. Because only identifiable bacterial taxa were used in the differential abundance and analyses, the authors suggest further research is required here.

This study found that grasslands exhibited significantly greater proportions of identifiable pathogenic bacteria compared to scrub. The abundance of the bacteria, however, decreased significantly with sampling height.

Individuals may be exposed to different aerobiomes depending on the type of habitat visited and human-scale height-based variation in environmental aerobiomes, the authors write. This is an important study highlighting where the priorities need to be in the context of better health, improved immunity, harbor diverse microbiome, restore green spaces, and ward off rapid pathogenic microorganisms and plan the urban spaces; implication for landscape management and public health. In this direction, efforts are needed to restore complex vegetation communities and host-microbiota interactions that provide multifunctional roles in urban ecosystems.

*Important Notice

bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.